“We Don’t Know What We Have Forgotten”: [A talk given by Michael Aaron Green to the Newburgh Historical Society on August 17, 2023]

Good evening and thank you for coming, I hope everyone has had an opportunity to look at the two portraits in the Crawford House dining room.

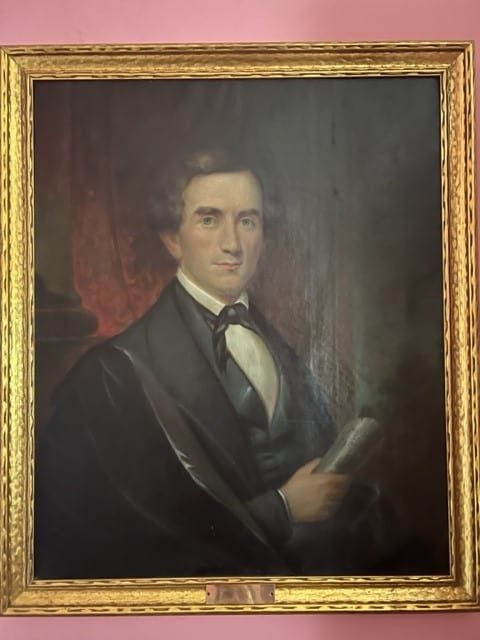

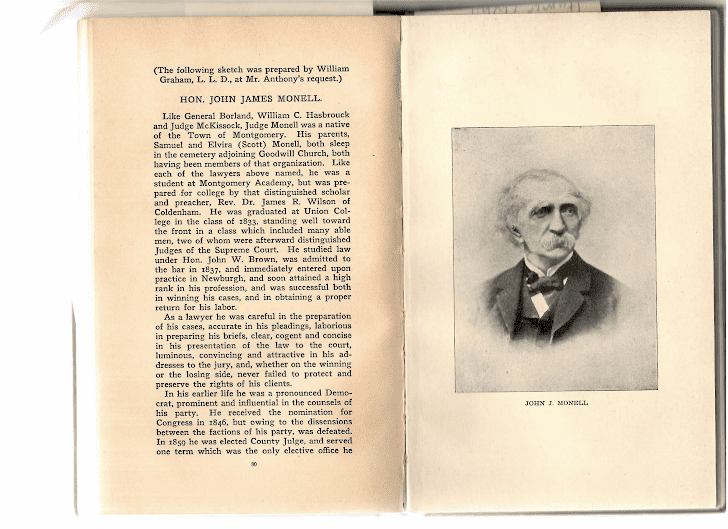

The older gentleman is merchant Samuel Monell, who was born in 1775 and died in 1840. The younger man is his son – then-aspiring attorney John James Monell, who lived from 1813 to 1885. J.J. Monell eventually served as an Orange County Judge. after which he was usually called “Judge Monell.”

The works are unsigned and undated, but I think we can safely say that both were painted in the 1830s, only a few years after David Crawford built this house. The pictures were donated to the Historical Society – entirely out of the blue — in the 1960s, but the subjects themselves had lived in this very neighborhood. So, I think it’s quite special that these artifacts found their way here.

The title of tonight’s talk is: “We don’t know what we have forgotten.” For perspective, I’ll just read a couple of sentences written about Judge Monell, after his death. They can be found on p. 159 of what everyone calls the “Nutt book”: Newburgh: Her Institutions, Industries and Leading Citizens”, published in 1891:

The lawyer’s arguments are seldom published, and the memory of them soon passes away, but whatever he does for the upbuilding of the community in which he is, lives on. Judge Monell took a large part in so many things that were for the good and prosperity of this city, that he cannot pass out of memory.

“Cannot pass out of memory.” Welcome to Orange County, New York, Land of the Forgotten Giants.

I became curious about Judge Monell, when I owned the 1868 Fullerton Mansion, The Fullerton had been built for a once-famous trial lawyer – Judge William Fullerton. And across the street, a few doors down, stood the circa 1840 Monell Mansion.

That two imposing homes for long-forgotten 19C attorneys had been built on the same block, just around the corner from where we are tonight, seemed to beg for further investigation.

I’ll get back to the lawyers of yesteryear, but first, let’s look more closely at the paintings.

Samuel Monell

As mentioned, Samuel Monell was born in 1775 and died in 1840. Hardworking and enterprising, he started out as a “chapman” or peddler before opening a store alongside a tollbooth, on the Newburgh-to-Cochecton Turnpike, where he also served as tollkeeper,

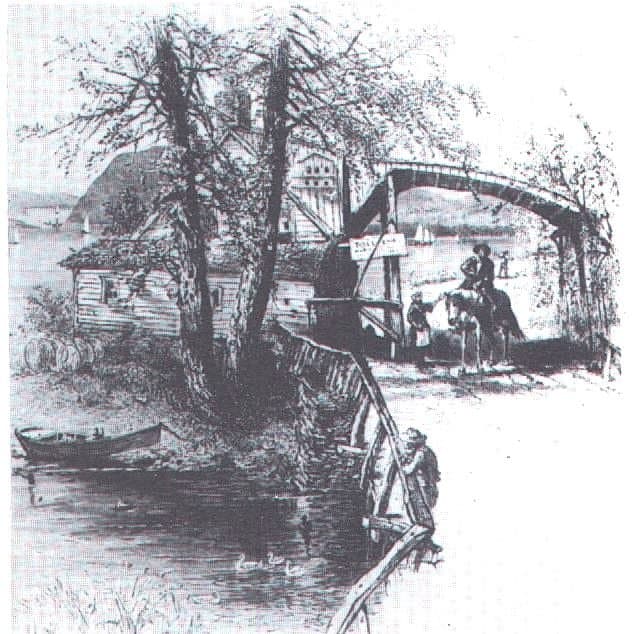

In its heyday, the Cochecton Pike connected the rich farmlands and natural resources of Orange County and beyond, to commerce with New York City, via Newburgh’s docks and shipping facilities. This drawing published in 1881 depicts the tollbooth over Quassaic Creek, on another turnpike heading south from Newburgh.

Quassaick Turnpike  Tollbooth

Tollbooth

I recently heard our City Historian Mary McTamaney telling some Crawford House visitors how – while stationed in New York City during the War of 1812 — David Crawford saw the potential in operating a shipping business out of Newburgh. This led to the wealth that paid for this elegant home, which is now our museum.

It dawned on me later that Sam Monell was part of the same ground-breaking transportation ecosystem as Crawford, having positioned himself at a key location along the turnpike, just a few miles west of Newburgh.

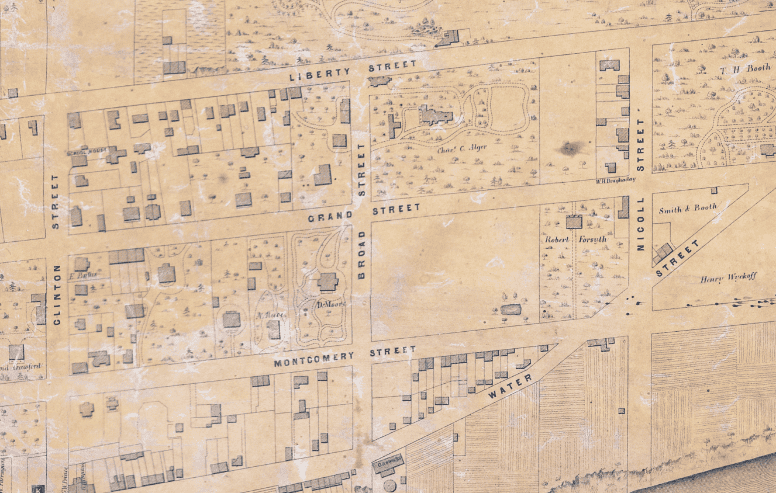

Over time, Samuel accumulated a variety of real estate and business interests. He and his wife Elvira moved to Newburgh and built a family home on Montgomery Street, at what used to be the corner of Third Street, roughly a half mile south of the Crawford House.

In the painting, Samuel’s attire is sober and respectable. Certain small touches, such as the silver cravat and gold-handled cane, reflect his age and status.

Little is known about Elvira. She was described as having a pleasing personality, which is a valuable asset in a merchant’s wife. Elvira presumably shared the early burdens and dreams of her husband. I can only offer this empty picture frame as a reminder of the indispensable roles of the nearly invisible 19th-century wives. We will also get to John J. Monell’s two wives, shortly.

John James Monell

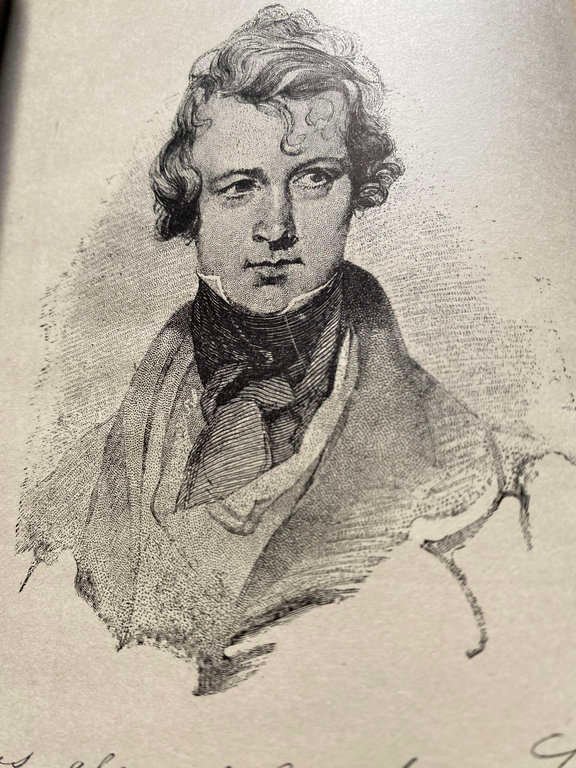

In his painting, the future Judge Monell is smiling, and his expression is forward-looking. But his formal garb and the weighty volume he’s holding suggests a scholarly and serious individual. Just for the sake of contrast, here’s a well-known dandy of the period – magazine writer Nathaniel Parker

Willis. Willis’ early years were full of scandal and controversy. In time he would move to Cornwall and become a friend of J.J. Monell. But as you can see, at the earlier stages of their careers, their public images could not have been more different.

Regarding Monell’s boyhood, The Nutt book says there was nothing remarkable other than the “marked purity of his morals.” This bit of dry humor obviously distinguished him from his more raucous school-boy peers, but also may help explain why the beautiful and high-minded Mary Elizabeth Smith later chose to marry him.

Still, the lengthy bio in the Nutt book omits an important detail – that Monell attended secondary school at the prestigious Montgomery Academy.

Why is this important? Because Monell’s time at the Academy overlapped with a budding genius: Newburgh’s Andrew J. Downing. This little factoid helps illuminate much that happened later.

Unlike Downing, Monell continued his formal studies, and graduated from Union College in 1833. He trained in law practice in the offices of John W. Brown, an acclaimed litigator and charismatic politician. Monell passed the bar exam in 1835 and was admitted to practice in the New York State trial courts in 1837.

So, this ‘portrait of a lawyer as a young man’ was likely intended to celebrate one of those milestones.

So, let’s talk about lawyers. Victorian-era New York was a tumultuous place. With all the tumult came a sea of litigation – both civil and criminal. And along with relentless economic growth, there were lucrative office practice opportunities as well.

But there were few law schools, and admission to the bar was a grueling process administered by existing practitioners. The result was something of an elite club, with much higher status than today.

The nearly identical, stately Court Houses of Goshen and Newburgh –  designed and built by master brick mason Thornton Niven in 1840 and 1841 – reflected the stature of the profession. They also provided the public with free entertainment, and sensational cases attracted overflow crowds.

designed and built by master brick mason Thornton Niven in 1840 and 1841 – reflected the stature of the profession. They also provided the public with free entertainment, and sensational cases attracted overflow crowds.

A wonderful relic of this period is a 1917 publication by Walter C. Anthony, a former Justice of the Peace who was also an early President of the Newburgh Historical Society. Anthony was so enamored of the prior century’s Orange County courtroom all-stars, that he created an entire volume of biographical sketches. The Monell bio emphasizes his ethical standards and – echoing the Nutt book – his commitment to the broader community. “No more public-spirited citizens lived in the town. His hand and voice and purse were freely given to every effort for benefitting or beautifying the city.”

We could spend hours on Monell’s career and accomplishments, but I think it’s his personal life that would be most fitting to discuss in this historic home, in this history-rich neighborhood.

We could spend hours on Monell’s career and accomplishments, but I think it’s his personal life that would be most fitting to discuss in this historic home, in this history-rich neighborhood.

Let’s go back to A.J. Downing, who would eventually become known as the “father of American landscape design”.

In 1838, Downing married Caroline DeWint, oldest daughter of a wealthy landowner who lived directly across the river in Fishkill Landing. She was also a direct descendant of the second U.S. President John Adams and his outspoken wife Abigail Adams. Downing immediately began building their fabled home, Highland Gardens.

Monell – who was still unmarried – built his own home on Grand Street in 1840, one block south of the Downing property. Steve Baltsas tells me that the stone mansion was likely built by Thornton Niven, who lived nearby on Montgomery Street, but It is generally believed that Downing consulted in the design. Certainly, Downing helped create the beautiful gardens that extended from the rear of the Monell Mansion down to Montgomery Street. Writer N.P. Willis would later offer readers of his popular magazine a glowing description of these grounds, which he called “Glen Monell”.

The next year — 1841 — Downing published his first book on landscape gardening. It was an overnight success and catapulted him – for the rest of his brief life — into national, and even worldwide, recognition.

Then, in 1842, Monell brought home his own bride. The former Mary Elizabeth Smith was the only daughter of a wealthy Connecticut lawyer. The Nutt book describes her as having “the genius of a poet.”

On the maternal side, she was descended from a long line of Congregational ministers, and her surviving poems reflect a serious turn of mind – covering a combination of religious and political subjects. I have to tell you that if Mary Monell were hosting this evening’s event, there might be famous writers in the room, but also good-natured grousing about the absence of alcohol.

On the maternal side, she was descended from a long line of Congregational ministers, and her surviving poems reflect a serious turn of mind – covering a combination of religious and political subjects. I have to tell you that if Mary Monell were hosting this evening’s event, there might be famous writers in the room, but also good-natured grousing about the absence of alcohol.

The opening of Washington Headquarters State Park was a very special moment for both John and Mary Monell. He had been active in the effort to establish the Park and, at the opening, gave a few dedicatory remarks before the flag was raised. And then, while the flag was being raised, a patriotic Ode written by Mary was sung by a large chorus.

Meanwhile, Downing’s fame and the hospitality at Highland Gardens were helping turn this neighborhood into something of a cultural Mecca. One famous visitor was Frederica Bremer, sometimes described as the Swedish Jane Austin. Bremer stayed with the Downings at the beginning and end of her 1849-1851 visit to the New World. She described the Downings as enjoying a circle of close friends, always laughing and exchanging visits to each other’s homes. She does not name the friends, but here, the Nutt book comes to our aid.

The Monell home is described as “a little paradise….” Readers are told that “Downing lived but a short distance away…. the two friends had their frequent meetings, and the two couples were as one.”

Writer Willis was also drawn to the area during this halcyon time, and in 1850 purchased a large and scenic piece of land, four miles south of Newburgh, where he began building his own fabled, and now lost, Idlewild.

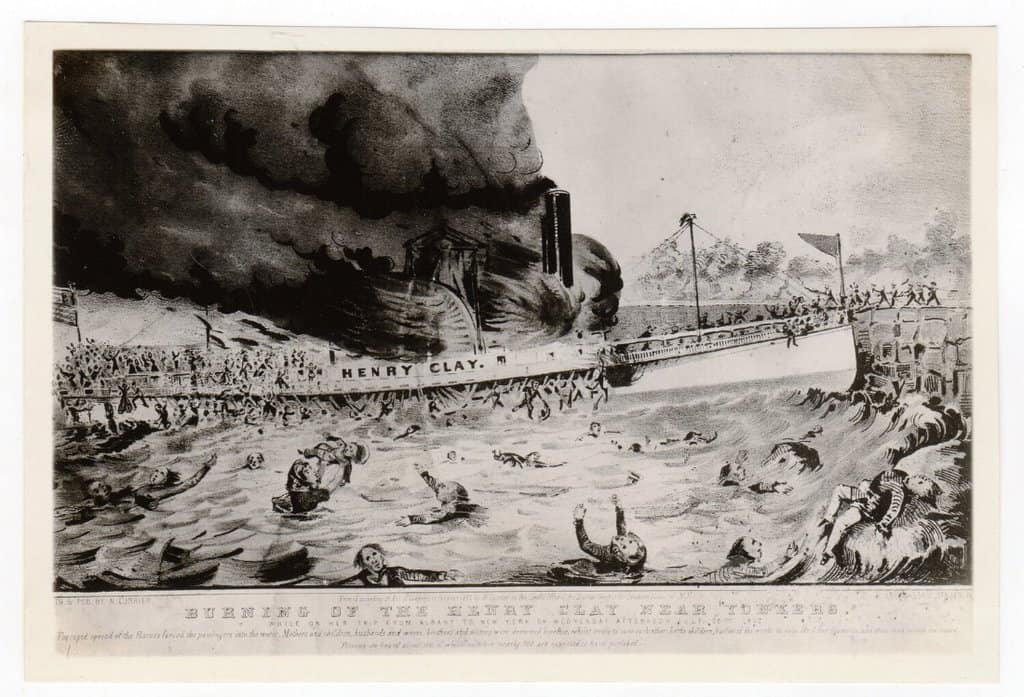

Newburgh’s magical moment came to a sudden and tragic end on July 28, 1852, when the steamboat Henry Clay burst into flames near Yonkers. M uch like the aftermath of the Titanic disaster, the public was shocked at the lack of safety precautions; and the newspapers bemoaned the loss of certain prominent passengers, especially 37-year-old A.J. Downing. His wife Caroline washed up on the shore alive, but she had also lost her beloved mother. Sources describe Downing’s bed-ridden and grief-stricken widow being tended by close friends, who again were never named. Of course, the Monell’s, along with Downing’s brother Charles and his own wife, are the leading candidates.

Downing’s financial affairs were a mess at the time of his death. The Anthony book describes an episode that I have not come across in other histories. Acting as coexecutor for his friend’s estate, Monell brought suit against the owners and captain of the Henry Clay. He retained Judge McKissock, an aging lion with few peers among Newburgh’s trial bar. McKissock told friends that he wanted to make this the defining case of his career. The trial judge was Monell’s own former mentor, John W. Brown. The defendants had distinguished counsel – a former New York State Attorney General. But during a Sunday break in the trial, he assessed the situation in that hostile Newburgh courtroom and persuaded his clients to make a settlement offer that was too generous to turn down.

For some time after Downing’s death, literary types continued to favor Newburgh. A nostalgic 1898 article in the Newburgh Register recalled a time when the Monell home witnessed gatherings at which worldwide celebrities met the men and women of the town. Mary was remembered as a “lady of extraordinary social, as well as literary, accomplishments.” The fare is described, however, as limited to rye bread and coffee.

For his part, an 1855 article by Willis described a picnic along the banks of the Hudson, in which his companions consisted of travel writer Joel T. Headley, magazine illustrator T.A. Richards, Newburgh lawyer John Monell, Mrs. Willis, and an unnamed “young woman of very remarkable beauty, from the city.” My money is on Mrs. Monell for the mystery lady.

But Mary Monell was also fated to die young. She passed away in 1857, at age 37, like Downing, possibly in connection with giving birth for the fourth time.

It caused some gossip in 1860 when widower John Monell married the widowed Caroline Downing. A few years later, they built a home across the river on the property where Caroline had grown up. The home – called Eustatia – was designed by Frederick Clarke Withers, who had emigrated from England to work with Downing shortly before the Henry Clay tragedy. It still stands on a bluff overlooking the bay, where they could look back across the water to the neighborhood where the two couples had been “as one.”

It caused some gossip in 1860 when widower John Monell married the widowed Caroline Downing. A few years later, they built a home across the river on the property where Caroline had grown up. The home – called Eustatia – was designed by Frederick Clarke Withers, who had emigrated from England to work with Downing shortly before the Henry Clay tragedy. It still stands on a bluff overlooking the bay, where they could look back across the water to the neighborhood where the two couples had been “as one.”

Judge Monell passed away in 1885. The twice-widowed Caroline Downing Monell devoted her remaining years to successfully campaigning for Newburgh’s planned park to be a suitable tribute to famous native son A.J. Downing. She never received proper credit for her efforts.

And there are no surviving portraits of either of J.J. Monell’s wives.

Visitors to Cedar Hill cemetery today can find A.J. Downing and Caroline lying side-by-side, beneath gothic monuments possibly designed by Downing acolyte Calvert Vaux.

But close by, there stands another unique monument, separated from the Downings only by enough grass for a picnic. It contains the last remains of John and Mary Monell, along with three of their children.

To finish, let’s get back to our paintings. Elvira Monell had remarried after Samuel’s death, but was still living at the Montgomery Street home, when she died in 1853. Her will bequeathed the portrait of Samuel Monell to their son John James. So, from that time until today, the two paintings have remained together.

Judge Monell and his first wife had only one surviving daughter, also named Mary. She married late in life and had no children of her own. Following her death in 1927, both paintings were left to a distinguished cousin, Gilbert Monell Hitchcock, who was a former two-term Senator from Nebraska and Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during World War I. In the 1960s. Hitchcock’s granddaughter, Mrs. William Dale Clark, of Palm Springs California, donated both to the historical society, which was then led by the dedicated Helen Gearn.

So here they are today in the Crawford House dining room, the proud father and his son with a bright future, in the neighborhood that meant so much to them and their loved ones. Perhaps those lines from the Nutt book — that Judge Monell “cannot pass out of memory” – will turn out to be true after all.

Special thanks to Josette Ramnani for her assistance with the images for this article, and to Joe Santacroce for making the Newburgh History Blog available to the local history community for publication of materials such as this talk.

.