In May 1864, the American Civil War was lurching towards its inevitable conclusion but the bloody toll was still mounting. Throughout New York State, families waited desperately for news of their loved ones or mourned their losses. In urban centers such as Newburgh, the community itself had been bitterly divided over the war, the draft, and Abraham Lincoln’s leadership.

With the end finally in sight, however, what could be a better way to lift everyone’s spirits than a grand musical evening?

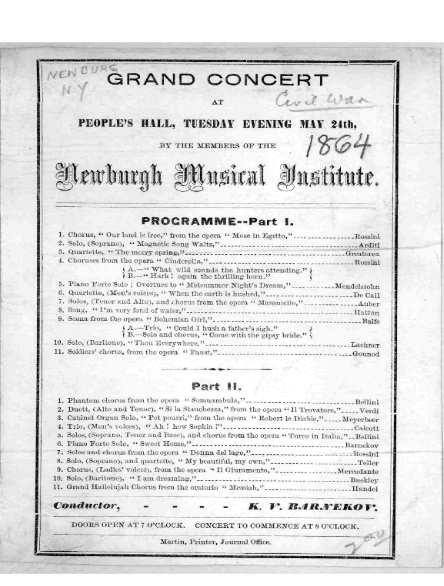

The recently formed Newburgh Musical Institute rose to the occasion with a May 24th concert at the People’s Hall. The crowd-pleasing selections consisted of 22 pieces by different composers, beginning with a Rossini chorus — “Our Land Is Free” — and concluding with Handel’s ”Messiah.” Conducting the performance: K.V. Barnekov.

Two pieces by local Newburgh musicians were on the program: “My Beautiful, My Own” by James L. Teller and “Sweet Home” by Barnekov. Teller (1839-1904) was a lifelong Newburgh resident who held a white-collar position for a large manufacturing concern. An 1890s article described him as the City’s leading amateur organist. “My Beautiful My Own” was dedicated to the members of the Institute and is his only known composition.

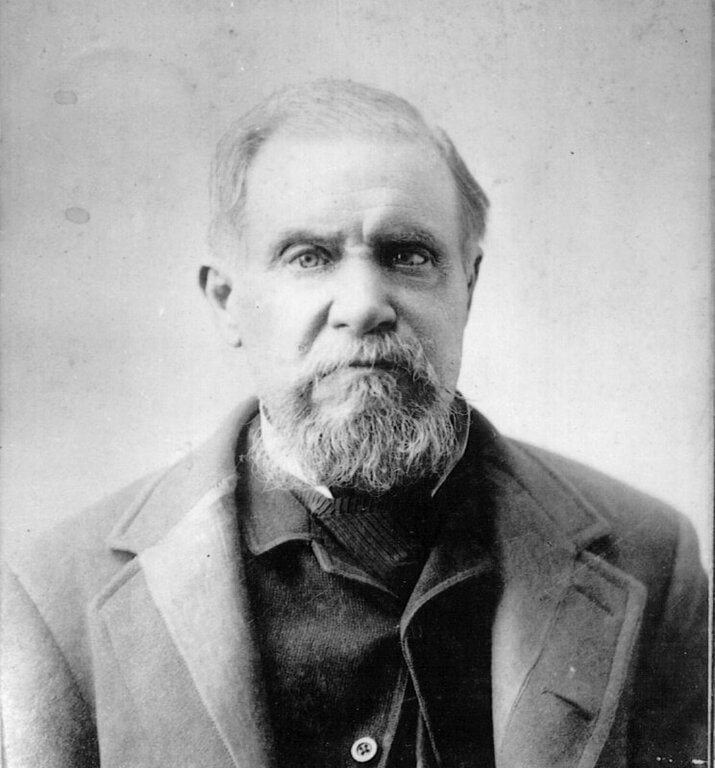

Swedish émigré Kiell Barnekov (1818-1897) was a newcomer to Newburgh. He had been living and composing in the U.S. for nearly 20 years. With one brief exception (for a lucrative teaching post in Missouri), he would remain in Newburgh for the rest of his life.

It is a little-known fact that during the second half of the 19th century, there were many active composers in Newburgh, as well as its sister Hudson River cities such as Poughkeepsie and Albany. Perhaps no one better embodies the creative, musical vitality of the era than Barnekov. He is all-but-completely forgotten today, but his traces are everywhere. It only takes a little effort.

There is something of an enduring mystery: why did Kiell Vollmar Barnekov, eldest son of Swedish Baron Kjell Christopher Barnekov (1781-1875), leave behind his wealthy and influential family, only to end up teaching music in Newburgh, New York?[1]

The Barnekov family of European nobility still exists today, with branches in Germany, Denmark, and Sweden. Their roots are traceable as far back as the year 1255. A 17th-century ancestor famously sacrificed his life in battle to save his king, supposedly saying: “I give my horse to the king, my life to the enemy and my soul to God”.

As to the future composer, there was one early incident in the Swedish Navy around 1838. According to surviving correspondence from his sister Anna, 19-year-old Barnekov clashed with his commanding officer, who had failed to take in the sails before an impending storm. The ship lost its masts and barely avoided sinking, but the young man’s own naval career was a permanent casualty.

Perhaps he wanted to leave behind a rigid and oppressive social order. In the wake of the excesses of the French Revolution and the devastating Napoleonic Wars, an ancient regime of powerful kings and aristocrats asserted an iron grip throughout Western Europe. Young Barnekov’s Sweden was a far cry from today’s liberal democracy.

Then again, maybe he simply wanted to pursue the opportunities available to a young man in the dynamic new nation across the Atlantic.

His personal family history might also have been a factor. The idea of “home” was clearly important to this composer, but the baronial estate in Spannarp, Sweden, may not have felt like much of a home for him. His mother had died when Kjell was only nine. The much older Baron Barnekov – 47 at the time – was soon remarried to his deceased wife’s sister. They went on to have several more children.

Barnekov arrived in Boston in 1842. He was 23. Although the composer maintained a lifelong correspondence with family members, he never returned to his homeland.

At the time of Barnekov’s arrival, America was experiencing an awakening of interest in European music. Boston was considered the young nation’s intellectual capital and introduced America’s first public school music education in the early 1840s.

The young composer immersed himself in the cultural life of his new abode. There are four surviving works from the Boston years. The earliest is a light-hearted waltz, with a French title: ”Valse a la Fantasie” (1844). This was published by W.H. Oakes, a short-lived local entity.

Three more pieces were published by Boston’s prestigious and fast-growing Ditson & Co. Two of these — “Souvenir de Julie” (1847) and ”Bath Waltz ”(undated) — reflect the elite tastes of the period.

”Polish Liberty March” (1848), however, honored the Poles’ struggle for freedom from Tsarist domination, during a terrible year of failed revolutions throughout Europe.

During this period, the Hudson Valley was famously a magnet for artists and literary types. So, it should not come as any surprise that there were composers aplenty among all the painters and poets.

The earliest evidence of K.V. Barnekov’s move to the Hudson Valley is his marriage, in 1851, to 17-year-old Sarah Jane Bunker of Albany, New York. Their first child, Charles, was born in 1855.

He now had a family to support. From 1855 to 1860 Barnekov held a full-time teaching position at Troy Female Seminary, where he taught piano, guitar, and organ. But this was no ordinary girls’ school.

The school’s founder, Emma Willard, was a visionary pioneer in women’s education. With the support of New York Governor Clinton, she presented a groundbreaking “Plan for Improving Female Education” to the New York State Legislature in 1819. Her goal was quietly revolutionary – to educate the female mind to the “utmost perfection of its nature.”

The Troy Female Seminary helped set off a “women’s seminary” movement throughout the country. As a result, generations of young women had access to serious subjects that had been reserved for young men, such as math and science.

Willard was a great lover of music and the renowned music faculty featured many well-regarded composers.

Barnekov continued to compose while teaching. Advertisements from the late 1850s for Hidley & Co., Albany’s leading music store and sheet music publisher, included various Barnekov items. “Sweet Home” (performed at the 1864 Newburgh concert) was described as ”a beautiful composition, well-adapted for the parlor, or teaching.”

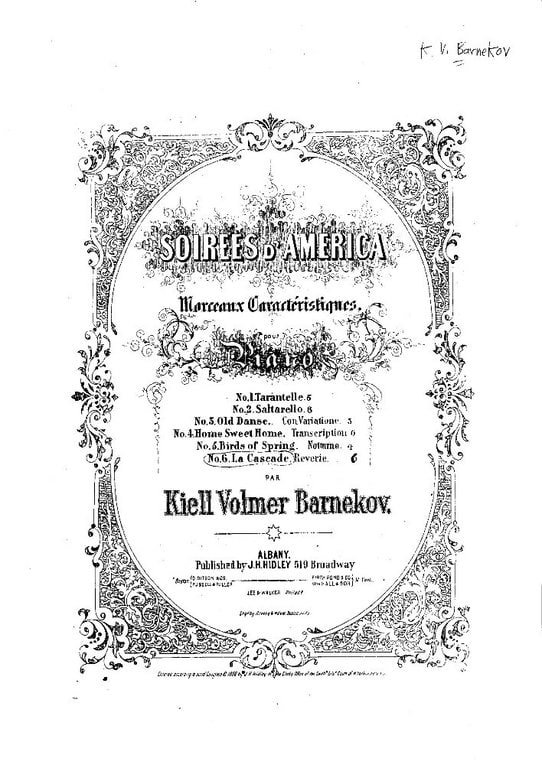

The only known surviving Barnekov piece from this period is “La Cascade”, which is in the archives of the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. The cover page, however, lists six Barnekov pieces, under the fancy-sounding French ”SOIREES D’AMERICA: Morceaux Characteriques”.  Each of the six items was clearly available for purchase through Hidley and other major publishers in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

Each of the six items was clearly available for purchase through Hidley and other major publishers in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

Barnekov would continue to compose for decades to come; however, this late 1850s time frame may have been his high-water mark with the music-loving public.

On the personal front, tragedy struck during his teaching and composing. His wife Sarah gave birth to a second child, a girl named Anna, in September 1857. Both mother and daughter died within a few months.

In an eerie echo of his own past, Barnekov married Sarah’s younger sister, Alice, in 1859. The couple moved 100 miles downriver to Newburgh and went on to have three more children. But the story diverges from his aristocratic origins in Sweden. Kiell, Alice, and all four children show every indication of being a tight-knit household, although living in modest circumstances.

Newburgh had a bustling port and served as a market town for the surrounding region. Decades of growth as a transportation hub and manufacturing center lay ahead of it. K.V. Barnekov became a mainstay of a vibrant musical community at a unique moment.

The burgeoning middle class had leisure time which led to unprecedented demand for entertainment and cultural experiences. Competition in the form of recordings and broadcasts was still decades away. (Those quaint, clunky Victrolas did not become widespread until the late 1890s. Radio eventually changed everything – but not until the 1920s.)

Beginning around 1840, steam-based printing led to explosive growth in the production of sheet music, along with newspapers and other print media. Advances in manufacturing made pianos and other instruments affordable, which increased the market for printed music.

Every respectable home had a parlor, where friends and family would gather for performances and sing-a-longs. Church choirs and other community singing groups offered a combination of social activity and entertainment.

Marching bands filled the streets for an endless stream of public venues. Large showy venues – from the stately churches to performance spaces, such as Newburgh’s People’s Hall and the later Academy of Music — hosted famous visiting performers as well as local talent.

It does not seem too far-fetched to call it a “golden era” for live, in-person music.

It does not seem too far-fetched to call it a “golden era” for live, in-person music.

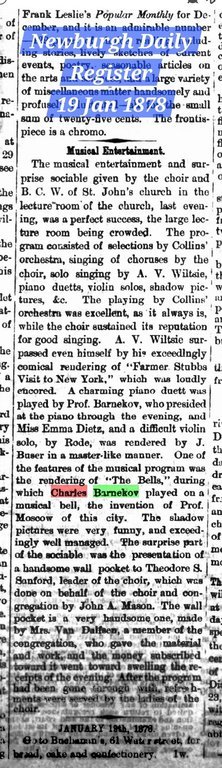

A January 1878 article in the Newburgh Register depicts one occasion in the community’s musical life. This was a gala/fundraiser for St. John’s Methodist Episcopal Church on Broadway. The church’s main hall had recently been rebuilt (and enlarged) after a fire. ”Prof.” Barnekov (who was also the organist for St. John’s) presided at the piano throughout the evening and played a duet with a woman who was likely one of his private pupils. His son Charles also appeared – playing a musical bell created for the occasion by Charles Moscow (an up-and-coming Newburgh bandleader, teacher, and music publisher).

The entire event was a rich blend of music, religion (in an undemanding form), and broader community social life.

K.V. Barnekov spent roughly 35 years in Newburgh. He never achieved great financial success but left behind a steady stream of compositions. These works provide a wonderful glimpse into the music and culture of post-Civil War Newburgh (and America).

A fun example — his 1868 “Gymnastic Waltz” was a Victorian-era version of today’s ‘workout’ music.

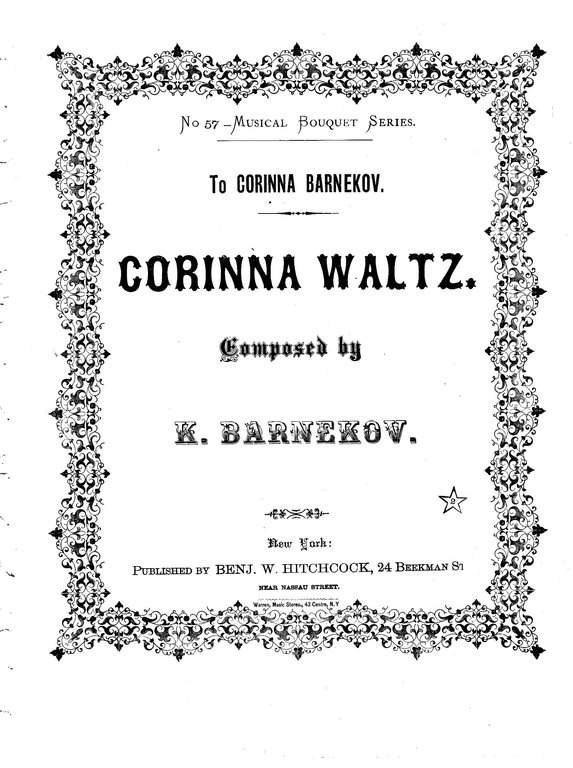

Another item in the Eastman School of Music archives offers a charming personal touch. “Waltz Corinna” (1869) was named after, and dedicated to, Barnekov’s five-year-old daughter, Corinna. The cover indicates it was published in New York City as part of a “Musical Bouquet Series”.

Another item in the Eastman School of Music archives offers a charming personal touch. “Waltz Corinna” (1869) was named after, and dedicated to, Barnekov’s five-year-old daughter, Corinna. The cover indicates it was published in New York City as part of a “Musical Bouquet Series”.

The background music for this article is a rendition by Albert Garzon of Barnekov’s “Beautiful Blue Hudson”, which was published in Newburgh in 1882. He dedicated it to his wife Alice, who undoubtedly shared his sense of

The background music for this article is a rendition by Albert Garzon of Barnekov’s “Beautiful Blue Hudson”, which was published in Newburgh in 1882. He dedicated it to his wife Alice, who undoubtedly shared his sense of

the mystery and timeless beauty of the river alongside which they had shared their life. The cover art is a gentle, nostalgic painting of Newburgh and its two-mile-wide bay, viewed from across the river.

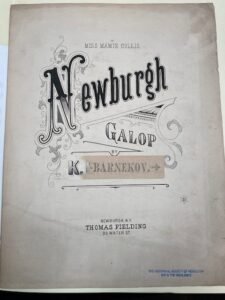

Newburgh got its turn with his 1881 “Newburgh Galop”. (Image at the beginning of this article.) The “galop” was a popular 19th-century dance and must have been in vogue in early 1880s America.

The next year – 1882 – was the occasion of a celebrated year-long U.S. visit and speaking tour by writer Oscar Wilde. Barnekov marked the moment with his own “Aesthetic Galop”.

Wilde’s aesthetics-based school of thought — “art for art’s sake” — still resonates today. The only known recording of a Barnekov work came about because a 21st-century Russian-German piano teacher was researching Wilde. Her rendition of Aesthetic Waltz can be found here:

Alice passed away in 1891, and Kiel in 1897. Both are buried in the Bunker family plot in Albany, along with first wife Sarah Jane and baby Sarah. The stately stone reads as follows: “Baron, Professor, Composer”.

It is difficult to assess Barnekov’s musical legacy, when so little of it has been recorded or even performed over the past 100 years or more. In general, though, it is hard to say which is more surprising: that so much music was created throughout the Hudson Valley during the 19th century, or that so little attention has been paid to it.

Far more work will be necessary before it can be said whether there is buried treasure in all the neglected sheet music, or whether generations of historians have simply missed the mark. Hopefully this article (and more to come) will spur further efforts.

Special thanks are owed to owed to Chris Barnekov, a direct descendant of the composer, who was so generous with his time and advice, and provided the photo of KVB at the beginning of this article. We are also greatly indebted to David Peter Coppen, Special Collections Librarian and Archivist at the Sibley Music Library, Eastman School of Music, for being so timely and responsive in providing access to the Barnekov items in their collection.

Michael Green is a retired lawyer and financial advisor, as well as Founding Board Member of Newburgh’s non-profit Fullerton Center for Culture and History. Albert Garzon is a Newburgh native and classically trained pianist, currently living in the Philippines. Green and Garzon are currently collaborating, under the auspices of the Fullerton Center, on the “Hudson Valley Historic Composers and Sheet Music Project”. Kris Sammarco and Eva Bonnabeau-Holdsworth have been providing invaluable volunteer assistance. Joe Santacroce, editor of the Newburgh History Blog, is always lending a hand in a wide variety of ways.

- For simplicity, this article will use the Americanized “Kiell Barnekov”. ↑