Mary Elizabeth Monell: The Forgotten Poet of Grand Street – By Michael Aaron Green

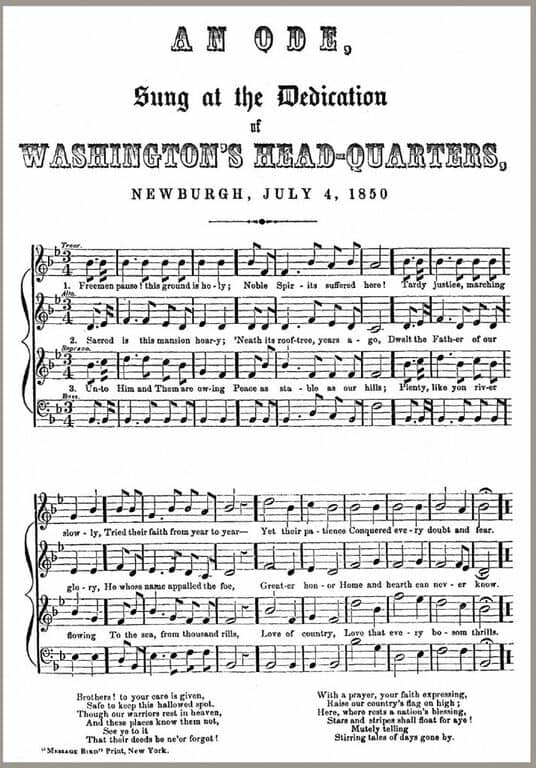

On a crisp, sunny spring day in 2016, the Newburgh Free Academy Madrigals assembled on the front lawn of a Dutch-era farmhouse and sang “An Ode” by Mary Monell. The fresh faces and fashionably black attire added a touch of youth and modernity to the centuries-old stone structure. The hymn-like tune has been sung at that location once before: at the July 4, 1850 dedication of Washington’s Headquarters State Park. The overall effect, as captured on video which can be seen in entirety here “An Ode”, is timeless.[1]

However, the author of the piece – Mary Elizabeth Monell (1820-1858) of 288 Grand Street – has been largely forgotten, even in the neighborhood where her home still stands.

It is a generally accepted reality of early New York history that there was not much written about women – unless they did something scandalous. So it should not be surprising that little is known about the brief life of Mary Monell: wife, mother, writer, and hostess of a literary salon.

At present, only a few of her written works have been identified. Taken together, they indicate a serious mind and a public voice on important occasions. And beneath the surface, perhaps, an author’s deep yearning to be taken seriously as something more than a lawyer’s wife.

Scattered sources refer to Mary’s abilities, mostly as afterthoughts to biographical sketches of her well-known husband, Hon. John J. Monell (1813-1885). John Nutt’s 1891 book about Newburgh’s “Institutions, Industries and Leading Citizens” states that Judge Monell’s first wife “had the genius of a poet”. Nearly 60 years after her death, Walter C. Anthony’s 1917 history of the attorneys of Orange County, mentioned Mary’s “considerable literary cleverness” (along with her with “unusual attractiveness”).

A bit more detail was provided in an 1898 Newburgh Register article, which looked back nostalgically on “the time, a half century or more ago, when Newburgh was something of a social center for literati of the country” and the Grand Street home of John Monell “witnessed gatherings” at which such world-wide celebrities as Hans Christian Andersen and John Jacob Audubon “met the men and women of the town.” Mary Monell was remembered as “a lady of extraordinary literary as well as social accomplishments.” Her “weekly conversations” were described as “always remarkable for intellect and wit”.

It seems long overdue to say a little something more about Mary. She was born on July 20. 1820, in Woodbury, Connecticut. Her father and his father before him were lawyers who also served as judges and were active in the heated politics of the day. On her mother’s side, there were five generations of ministers, stretching back to the distant Puritan past, and two of Mary’s uncles were known writers. One of the uncles, Samuel Griswold Goodrich, made a great deal of money from a popular line of children’s books published under the name ‘Peter Parley’ and was one of the many literary visitors to the Monells’ Newburgh home.

While Mary was raised in an atmosphere that was rich in books and ideas, a college education was a distant dream for a bright young lady in the 1830’s. Intellectual nourishment in the form of poetry, though, was readily available.

Samuel (‘Peter Parley’) Goodrich’s 1856 memoir describes Mary’s grandmother’s love of poetry and includes a long poem written by one of his sisters – probably Mary’s mother — the former Mary Anne Wolcott Goodrich.

Litchfield (Connecticut) Historical Society records note that Mary Anne showed considerable literary potential herself.

On the surface, her husband John James Monell was very much in the mode of Mary’s father and grandfather.

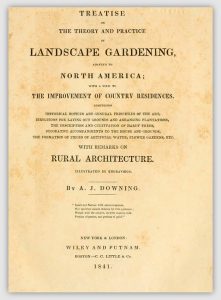

Monell was a civic-minded gentleman and prominent lawyer who served one term as a county judge. By the time Judge Monell married Mary in 1842, he had already built the Grand Street home, apparently with the close guidance of his dear friend, A.J. Downing. And for the next 10 years, Mary was part of a charmed Newburgh circle surrounding the charismatic Downing, whose many published works came to be a dominant influence on American life throughout the 19th century.

The two men had been friends since their teens when they studied at the nearby Montgomery Academy. Monell had continued his education and graduated from Union College in Schenectady in 1833, while Downing had left the academy at age 16 and joined his brother in the family’s Newburgh-based nursery business.

One source indicates that Monell and Downing had competed for the same prize – Caroline Elizabeth DeWint (1815-1905). She and Downing married in 1838. Historians note that the still-unknown Downing married advantageously. Caroline’s mother’s family tree included two U.S. Presidents, and her father was one of the wealthiest men in the mid-Hudson Valley. But Mrs. Downing’s intellectual gifts and force of character made her a formidable figure on her own merits.

By the time of the Monell wedding in1842, Downing had published his pioneering “Treatise on Landscape Gardening as Adapted to North America” and was on his way to a unique position as the young nation’s leading authority on home, garden, and civilized life.

Thus, with Mary’s arrival in1842, the neighborhood now boasted a pair of power couples who were intimate friends. The Nutt book tells readers that “the two households were as one.”

The enormous, gothic Downing residence faced Liberty Street (across from present-day Mount St. Mary’s College), while the grounds extended to Grand Street. What later maps referred to as the ‘Downing Castle’, and its surroundings, were intended to be a showcase for an empire of aesthetic ideas. The plantings and nurseries, the fabled winding paths, trees and artfully placed Hudson River overlooks — reached almost to the boundaries of the Monell property.

The Downing mansion dominates the block of Liberty Street between Broad and Nicoll in this map. The Monell home is visible on Grand, the fourth building on the left heading from Broad to Clinton, with the grounds extending to Montgomery.

Obviously reflecting Downing’s influence, the smaller grounds behind the Monell house (known as the “The Glen”) were also considered extraordinary and were widely praised by visitors like Nathaniel Parker Willis, the most popular American magazine writer of the period.

Lawyer Monell and his poet wife made a fine team. One common interest was the history-laden site at the base of Grand Street, less than a mile from their home. The Dutch colonial era ‘Hasbrouck House’ had served as George Washington’s Headquarters during the tense final period of the Revolutionary War, and the 1850 establishment of the park by the State of New York was a major milestone. The building – with all its deep symbolism – was in foreclosure, and at risk of being sold. For the first time in U.S. history, a government entity took direct responsibility for operating a historic site.

Some of Washington’s actions in Newburgh had helped define the future of the nation – for example, his furious rejection of a proposal that he become a constitutional monarch. According to historian (and Newburgh native) David Schuyler: “To 19th century Americans… Washington’s Headquarters became a symbol, a shrine to American republicanism.” Also, when the Park first opened, the nation was facing another fundamental threat — the secessionist movement in the slaveholding states.

The July 4, 1850 dedication ceremony was attended by an estimated 10,000 people and began with a performance of Mary’s Ode. Her lyrics treated preservation and remembrance as sacred duties: “Freemen pause! This ground is holy/….to your care is given/Safe to keep this hallowed spot/Though our warriors rest in heaven/…. / See ye to it/That their deeds be ne’er forgot.”

The final stanza commands undivided loyalty to the flag: “With a prayer your faith expressing/Raise our country’s flag on high/Here, where rests a nation’s blessing/Stars and Stripes shall float for aye….”

Another important surviving work is her tribute to the beloved Downing, who died at age 37 in a steamboat disaster. Mary’s memorial essay was published, without editing, in The Knickerbocker, the most prestigious literary magazine of the day. Her description of the loss must be taken as heartfelt:

[T]hose who knew him best felt that his work was only commenced. His large and commanding intellect, his far-reaching views, his unaccomplished plans, seemed to demand a long life of industry for their fulfillment. Oh, how much hope and promise is ended in his early grave!

Perhaps she articulated her own poetic ideal in this description of Downing’s writing:

There is scarcely another writer in America whose language is so crystally pure, so simply direct, and yet so finished and elegant, as Mr. DOWNING’S. It flows like a limpid stream, without effort, to the sound of its own music.

In the same vein, she creates an intimate connection between the aesthetics of a landscape and choice of words, while referencing the struggles known to most writers:

His unerring and intuitive taste saw at once the utmost possibilities of every landscape, and the direct means to attain the desired result. Neither was it a wearying or anxious process. Beauty nestled in his thoughtfully fledged and needed only the fitting word to soar at once into air and sunshine.

The Nutt book comments that John Monell’s tumultuous professional life was offset by a “happy” social life, but the Monell personal history was filled with loss. Mary gave birth four times, but only one child survived to adulthood. And six years after Downing’s passing, Mary herself died (probably while giving birth) in October 1858.

Only one other item written by Mary has been found to date: a religious-themed funeral hymn called “Gone Home”. It was published in July 1858, and identified only by the initials “M.E.M.” Commemorating the loss of a dearly loved aunt, Mrs. A.G. Whittlesey, who was the editor of a publication called “The Mother’s Magazine”, the tone is solemn and mournful — “Gone Home! Gone Home! She lingers here no longer”. Invoking Christian salvation, the work seems to unintentionally foreshadow Mary’s own death a few months later — “And if thou wilt, in tender, pitying favor, hasten the time when we may rise and go.”

The hymn apparently found favor in Congregational circles; it was reprinted in hymnals into the early 20th century, although without attribution.

Two years after Mary’s death, in a twist that must have been the talk of the mid-Hudson Valley, the widow Caroline Downing married the widower John Monell in February 1860. They lived briefly in the Monell house, but then built a new home, directly across the river, on her family’s property. The lovely Eustatia affords sweeping views across the Hudson to the Newburgh side, so the occupants could look across and remember the evanescent moment when “the two households were as one” and the best minds in the country visited both homes.

The Downings had no offspring, and John and Mary’s only surviving daughter, Mary Goodrich Monell, moved with Caroline and John to Eustatia. She married very late and did not have children. (Unsurprisingly, the husband was a lawyer who wrote law-related books.) The absence of any direct descendants for either couple helps explain the disappearance of the correspondence, journals and other artifacts that would tell us more about Mary.

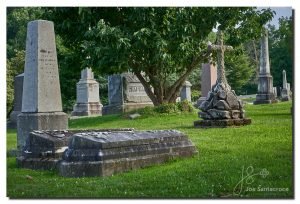

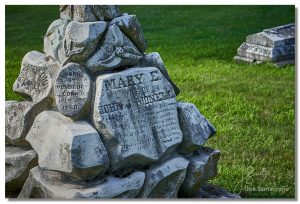

As noted, the Monell mansion still stands but the Downing residence, and all the storied landscaping, have long since vanished. The two couples are buried in adjacent, paired graves in Cedar Hill Cemetery — each with their original spouse.

A published history of an 1878 reunion of New England’s venerable Ely family (to which Mary belonged on her mother’s side) included the full text of “Gone Home”, along with a nostalgic look-back at its author:

Her death removed a star from a brilliant social constellation. No portrait has ever done justice to those large dark eyes of velvet softness which led captive friends and strangers. Her poetic gift was most delicate and responded whenever her taste was pleased or her heart touched.

The author ends on a tantalizing note, telling readers that “Gone Home” was chosen for inclusion “not as her best, but as her last.”

It seems likely that other poems are still extant, but unidentified. Newspapers of the day routinely included poetry, and there was no shortage of literary magazines.

Let the search begin!

Author note: Special thanks for Josette Ramnani, 21st century Grand Street resident, for her invaluable help with the research for this article. And, as always, much gratitude to the incomparable Joe Santacroce for creating the Newburgh History Blog and providing an outlet for stories like this.

[1] The performance was arranged by local historian Joe Santacroce in connection with his documentary film about the Park: “The Mansion on the Hill”, which can be found here: “An Ode”.