Introduction.

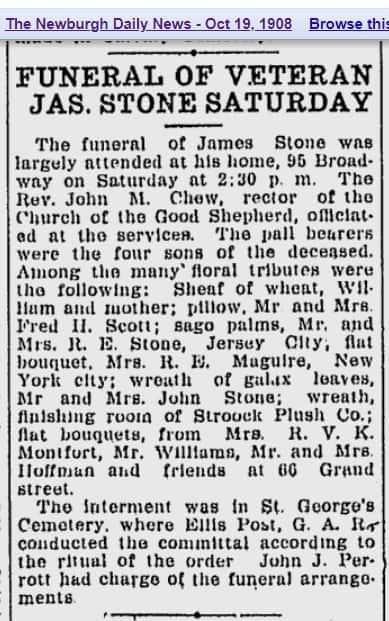

On October 17, 1908, a brief death notice appeared in the Newburgh Telegram:

James Stone, a well-known Union veteran, died aged 63. He went to the front with Capt. Fullerton, as a member of Company D, Third New York Volunteers. After his enlistment expired, he enlisted in the 7th New York artillery. He was taken a prisoner and confined in Andersonville for 8 months.

Although the Civil War had ended 43 years earlier, the writer evidently assumed that at least some local readers would recognize three separate reference points: Newburgh’s Captain Stephen Fullerton; New York’s 7th Artillery (heavy) Regiment; and the notorious prisoner-of-war camp at Andersonville. For each was — in its own way — a symbol of the War Between the States’ terrible cost in lives and suffering.

A 21st-century reader might need a little more background.

War On.

What Northerners sometimes called the War of Secession began in an atmosphere of confusion, posturing, failed diplomacy and behind-the-scenes maneuvering. But on April 12, 1861, shore batteries in Charleston, South Carolina opened fire on the blockaded and starving garrison in Fort Sumter, which surrendered the next day. The Northern states were galvanized into action and President Lincoln’s call for volunteers was answered with enthusiasm. This, in turn, reverberated negatively in the South. The pivotal State of Virginia joined the secessionists, and long terrible war was on.

Captain Fullerton’s Company B.

Newburgh’s Stephen W. Fullerton was a promising young attorney, of whom great things were expected. He must have been a naturally-gifted public speaker; when the war commenced, he was only 24, but was already completing his first term in Albany as a State Assemblyman. Fullerton not only answered Lincoln’s call for volunteers, he recruited an entire company from Newburgh and surrounding communities on both sides of the Hudson River.

At that stage of the war, the North had no real army and few trained officers. The South had stronger military traditions and many of the U.S. military’s more experienced officers chose loyalty to their native states, over the Federal cause. Early volunteer companies in New York chose their leaders. They often elected the person who had led the recruitment effort. Thus, the young lawyer-politician became Captain Fullerton of Company B, New York Third Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

It was widely assumed that a war between neighboring states could not last very long, and the members of Third Volunteer Regiment signed up for two-year terms.

Newspaper clippings describe the regiment leaving Albany to a “great ovation”. Upon arrival in New York City, they marched proudly down Broadway, where a great crowd admired their fine bearing and the brightly-colored regimental flag and banners.

There were some harbingers of trials to come – for example, the military bureaucracy had failed to provide them with rifles before leaving Albany. In New York City, they were offered antiquated muskets, which they sensibly rejected, and their departure was delayed until appropriate weapons were supplied.

The regiment saw some early action at the battle of Big Bethel. The result was inconclusive, but at one-point, inexperienced Union commanders had provided conflicting instructions, and Third Regiment experienced losses from friendly fire. By all reports, however, Captain Fullerton conducted himself bravely and led his men unflinchingly in the face of enemy guns and cannon.

It was camp life that killed Captain Fullerton, rather than bullets. In 1862, the regiment was stationed at Fort McHenry near Baltimore, where Fullerton fell ill. As his condition worsened, he was sent home to Newburgh, where he died in a state of delirium diagnosed as typhoid fever, on September 11, 1862.

Newburgh’s Fullerton Avenue has carried his name since 1868.

Private Stone Goes to War.

James Stone’s parents had emigrated from Ireland in the 1850s, along with James and a younger brother. His father’s occupation is described in census records as “laborer.” The 1860 federal census shows James as the oldest in a family of eight children, which may have been a motivation for him to enlist in Captain Fullerton’s company.

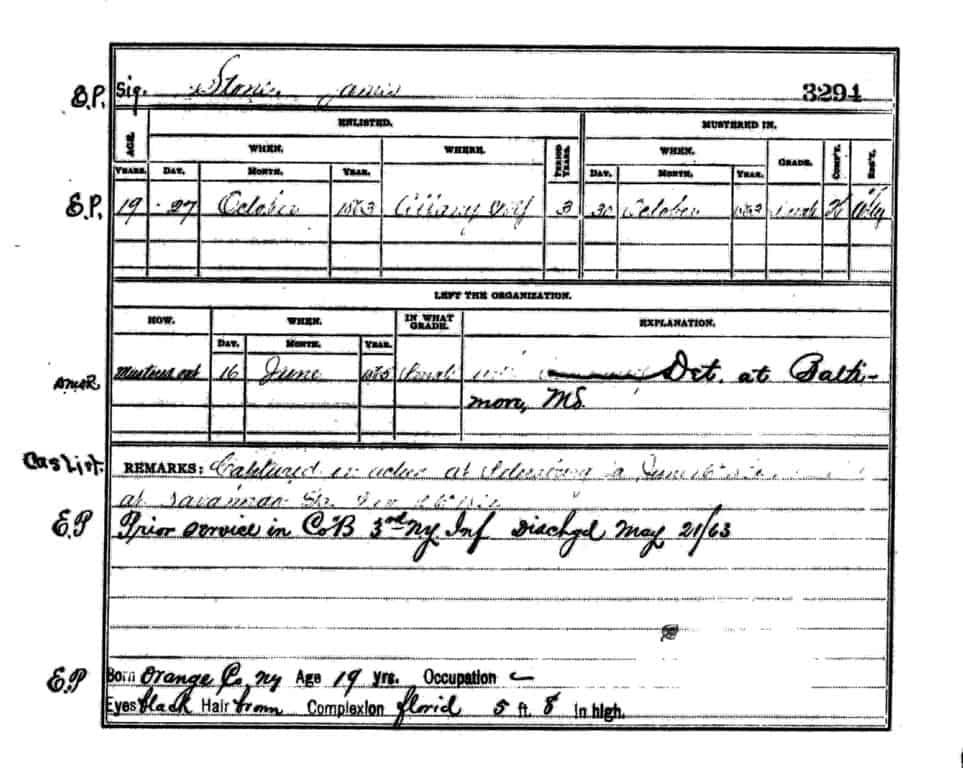

Army records show that Stone was enrolled in Newburgh on May 14, 1861. His age is shown as 19, but he was only 17.

For much of Private Stone’s enlistment period, the Third Regiment was kept busy guarding forts, especially the strategically important Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula; but they saw relatively little combat action between Big Bethel and the expiration of the initial two-year period of service.

Other Northern regiments were less fortunate, and as the war dragged along, it became much more difficult to recruit fresh troops, eventually leading to the institution of a controversial draft. In May 1863, Stone’s entire regiment was brought back to Albany, with substantial bounties offered for re-enlisting. Anyone did not re-enlist was paid for their time in service and discharged.

James Stone may have had personal reasons for not re-enlisting immediately, and it seems likely he spent some time with his family in Newburgh.

But as noted in the 1908 article, Private Stone re-upped. Records show him being mustered into Albany-based Company H, 7th Artillery (Heavy) Regiment (also known as New York 113th Volunteer Regiment) on October 23, 1863. He was recorded again as age 19.

Perhaps he was unduly optimistic about the future of the war. A tragic fate awaited the 7th Artillery.

Unlucky 7th.

The summer of 1863 had marked a turning point in favor of the Northern side. The simultaneous capture of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River by General Ulysses Grant and defeat of General Lee’s Confederate army at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania (both on July 4th) sealed the ultimate outcome of the war. But the final, bloodiest phase of the war still lay ahead, as Lee’s Army dug in and defended the precious home territory.

General Grant was now commander-in-chief of the Union Army. He had superior numbers and a knack for brilliance at battlefield maneuver, but faced a desperately determined resistance. Their defensive use of trenches against Grant’s offensive efforts foreshadowed the great losses that European armies would suffer in World War I. In addition, natural barriers like swampy ground and scrubby, roadless forests provided little room for the kinds of encircling tactics that had succeeded for Grant on the war’s western front.

These stalemate-like conditions and Grant’s willingness to sacrifice his troops for ultimate victory in a war of attrition were the cause of much carnage, which Private Stone was fortunate to survive.

As of April 1864, 7th Artillery was manning the defenses in Washington, D.C., against an attack never came; but then they were suddenly dispatched into the heart of merciless combat between two unyielding adversaries.

The reports back to the newspapers in Albany from the battlefields around Spotsylvania Courthouse (May 19-21) are harrowing and filled with ghastly images of death, bloody wounds, and amputations.

The simple numbers make for grim reading. As described by one writer: “[o]n leaving Washington 15th ult. our morning report showed an aggregate strength of 1850 officers and men; today we report 932 men present for duty.”

The casualties included their popular commander, Colonel Morris, who was picked off by a rebel sharpshooter while inspecting the lines.

Further losses were yet to come. Army records show that Private Stone was captured at Petersburgh on June 16th, 1864. What happened there was described at an Albany gathering of survivors in 1912:

On the 16th, a general attack was ordered along the line which was only partially successful. On the part of the line assigned to the Seventh, it was unsuccessful. They charged right up to the works, were in the ditch, were then flanked and ordered to surrender…The regiment at this fight lost 35 killed, 105 wounded and 304 taken prisoner.

Prisoner-of-war.

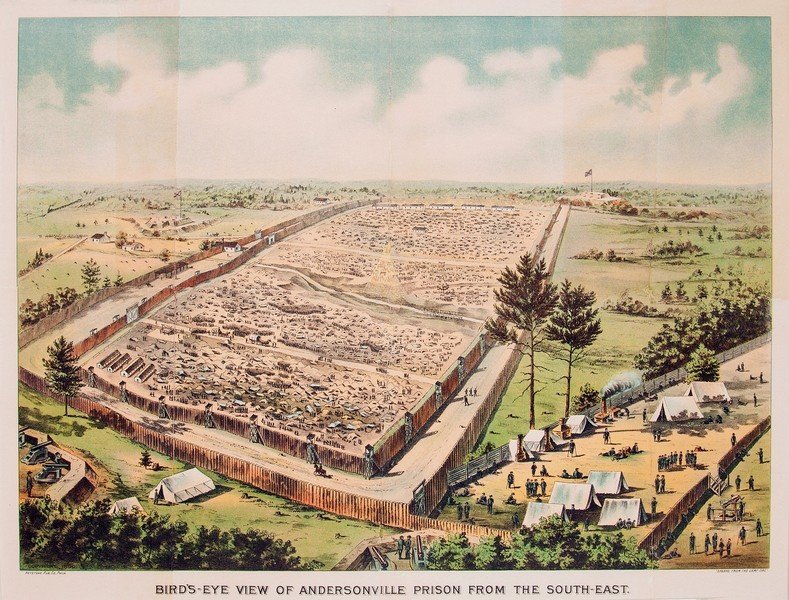

Stone was no longer at risk of being killed or wounded in combat, but — as we learn from that 1908 Newburgh article — he was confined in Andersonville. The inhuman conditions in that facility were as much a part of post-Civil War folklore as the Bataan Death March following World War II. The National Park Service website for the Camp Sumter-Andersonville historic site has this summary:

Located deep behind Confederate lines, the 26.5-acre Camp…was designed for a maximum of 10,000 prisoners. At its most crowded, it held more than 32,000 men, many of them wounded and starving, in horrific conditions with rampant disease, contaminated water, and only minimal shelter from the blazing sun and the chilling winter rain. In the prison’s 14 months of existence, some 45,000 Union prisoners arrived here; of those, 12,920 died and were buried in a cemetery created just outside the prison walls.

Of course, by 1864, the Confederacy was desperate of goods and having difficulty feeding its own soldiers and the civilian population. But conditions at Andersonville deviated so greatly from civilized norms that its commandant, Captain Henry Wirz, was later tried and hanged for war crimes – the only person executed for war crimes committed during the Civil War.

War Over.

Army records further show that Private Stone was paroled on November 26, 1864, at Savannah, Georgia. The terms of parole would have meant he could not engage in combat, so the war was essentially over for him following his release from Andersonville.

He was finally mustered out with his detachment on June 16, 1865, at Baltimore, Maryland and free, at age 21, to return to Newburgh and his family.

An Entire Life Ahead.

He was only 21, but weighty responsibilities awaited him at home. An 1865 census shows him as the head of the household which included six younger siblings. Although he had survived the war, his parents were apparently gone. His employment is listed as “brickmaker.”

Soon enough, he had his own family. The 1875 Federal census shows him supporting his 22-year old wife Harriet and three boys. Eventually, there would be a total of eight children (six boys and two girls).

His occupation is listed as brick-mason. Presumably, he had a hand in some of the 19th-century brick homes and rowhouses that can still be found throughout Newburgh.

It could not have been easy to raise a large family on a mason’s wages; a separate record from the 1880 census shows two boys named James and John Stone in an institution for destitute or homeless children.

Obviously, we don’t know if ex-Private Stone woke up every day thankful to be alive or if he sometimes to succumbed to various manifestations of what we now call PTSD. But the personal history indicates a commitment to work and family, and the 1908 description of him as a “well-known Union veteran” suggests he had shared many stories about his early years in the midst of history and war.

His widow Harriet passed away in 1914; the 1910 census showed several of the children still living with her.

The author hopes this article will somehow find its way to James’ and Harriet’s descendants.

Special thanks to Kris Rizzo Sammarco, local Newburgh history fan, who unearthed the 1908 newspaper article, which made this research possible.

And thanks many-times-over to the Newburgh History Blog for providing a forum for this story.

By: Michael Aaron Green

January 22, 2019