A novel entitled, Stealing The General, about a Civil War spy escapade contains references to the notorious “Newburgh Murder” or “Newburgh Horror” that was headline news throughout the east in 1870.

At 6:30 on the evening of August 30, 1870, a houseguest of the John Seaverns family quietly strode into their dining room on Grand Street in Newburgh and shot his host dead as he ate his supper across the table from his wife. Mrs. Seaverns was not attacked. Mr. and Mrs. Seaverns were a pleasant and respected couple who had no known enemies. John Seaverns was a brilliant inventor and successful manufacturer who owned two local enterprises, the Arlington Paper Mills eight miles southwest of the city and a Newburgh factory that produced paper-making machines. He had just that week shipped the largest such machine ever manufactured in America from this Newburgh plant. Seaverns paper-making machines were used exclusively by the U.S. Mint to create our national currency because of their quality.

Despite material success, John Seaverns and his wife labored with a mentally handicapped son who had recently been discharged to their care from a hospital for the insane. The Seaverns moved from Massachusetts where their son had been hospitalized and were fixing up their lovely old townhouse at 116 Grand Street across from Campbell Street (now part of the city parking lot). Masons and carpenters were coming and going through the home during the month of August and so was a disturbing houseguest, Robert Buffum. Buffum had been an inmate with young Joseph Seaverns in the Worcester, Massachusetts asylum. He had entered with an address of Salem, Massachusetts, but Buffum had led a wandering and quite horrific life.

A poor and neglected Ohio farm boy, he had enlisted in the Union Army to change his circumstances. That he did. He was recruited in 1862 to join a band of guerrillas who would infiltrate the Confederacy and disrupt the delivery of supplies thus crippling the war effort and bringing Jefferson Davis’ government to its knees. “Andrew’s Raiders”

plotted their border crossings and their rendezvous points and devised a scheme to steal “The General,” a busy workhorse of a steam engine, and ride it across the southern rail routes destroying tracks and blowing up bridges. They succeeded in the theft and rode for one glorious day through Tennessee and Georgia wreaking some havoc. An indomitable engineer on the Western and Atlanta Railroad line pursued them against all odds, however, and they were captured. (This exciting Civil War adventure, the story of the Andrew’s Raiders, known as the “Immortal 22” was made into a movie, “The Great Locomotive Chase,” starring Jeffrey Hunter and Fess Parker. Newburgh’s murderer, Robert Buffum, is featured as one of the raiders before his descent into madness).

Capture and imprisonment destroyed Robert Buffum and perhaps more of his companions. They were shackled and left naked in a pit dug in the ground under Libby Prison for weeks. Eight, including their leader, were hanged. Some were whipped nearly to death. Six were finally exchanged including Robert Buffum. All 20 military members of the raiding party were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor and the survivors were the first recipients of that newly-minted medal in March 1863.

After the war, Robert Buffum married, had children and wandered the country doing odd jobs. His volatile temper grew worse and he told strangers that killing was his business and he would as soon kill a man as a dog. He shot a man in the face in Ohio before he came east but, since the man suffered only minor injuries, Buffum was not incarcerated long. Eventually, in Massachusetts, his wife had him committed to a hospital where he met a gullible young man from Newburgh, Joseph Seaverns, whom he befriended and promised to visit “on the outside.” Young Seaverns got stronger and was sent home and Buffum calmed his temper and secured a release too. As Mr. and Mrs. John Seaverns refurbished their home and welcomed their fragile son back, a seething Robert Buffum planned his course to Newburgh for a season of freeloading on his chosen hosts.

He wrote a polite letter asking to visit young Joseph and the unsuspecting parents agreed.

In September 1870, the county courthouse at 123 Grand Street was the center of everyone’s focus in Newburgh. Inside was a prisoner named Robert Buffum, a bizarre man who had to be transferred from spot to spot inside the old basement jail and then upstairs in court chambers and sheriff’s offices to keep him safe from himself and others.

Buffum shot and killed Newburgh businessman John L. Seaverns at the latter’s supper table on the evening of August 30, 1870. The shot from a large pistol Buffum had purchased that day rang out loudly around the Grand Street neighborhood and immediately attracted the attention of Undersheriff Tuthill who was sitting on the porch of the courthouse. Tuthill ran across the street following the sound and saw poor Mrs. Seaverns run out her door at 116 Grand Street screaming for help. He dashed up her front porch and saw a man standing at the head of the stairs holding a pistol and glaring back at him. Unarmed himself, Tuthill retreated and ran to get Marshall Goodrich, the watch commander at police headquarters down on First Street. Together they returned to the Seaverns house and, with only one club and one pistol between them, took the murderer into custody and marched him across the street to a jail cell. Tough guys kept the peace in 1870.

Meanwhile, a distraught Mrs. Seaverns sent someone to fetch Dr. Culbert, the nearest physician, whose home and office were on the corner of Grand and Second (today the burned out shell of the former City Club). The doctor hurried south down the half-block on Grand to the Seaverns home and pronounced the victim dead. The city coroner was called and immediately convened a grand jury. Unlike today, the protocol for such a crime was to recruit jurors on the spot and muster them at the crime scene to inspect, deliberate and determine charges. Michael Hirschberg, a prominent attorney was first summoned from his home at 41 Second Street to be foreman of this panel. Just after poor John Seaverns breathed his last, his grand juror neighbors were standing in his dining room interpreting the scene and listening to witnesses while Seaverns’ body still sat holding a butter knife and slice of bread.

Several witnesses and neighbors knew of Seaverns’ recent houseguest, Robert Buffum, and all agreed he was a troubling man. Having been in Newburgh less than two weeks, Buffum was already known around downtown bars as a braggart. He had been taking young Joseph Seaverns out to the taverns and this intemperance and its effects on the young man had caused John Seaverns to ask his son’s “friend” from the Massachusetts Lunatic Asylum (where they had each been treated) to leave town as soon as possible. Seaverns had paid Buffum to leave, giving him the money he said he needed for his passage “out west.” But Buffum didn’t go that fateful day of August 30, 1870. Instead, he went to a hardware store on Colden Street and purchased a gun, deliberately selecting a heavy “old-fashioned” one perhaps because of its cost or because of his familiarity with such a model. The Colden Street barber whom Buffum visited for a haircut, shave and shampoo just after this purchase and before he strode up the hill to commit murder commented on the unwieldy size of the gun Buffum was showing off.

Like the nation in these years just after the Civil War, Newburgh must have been a wilder city with a higher tolerance for openly armed residents than we realize when we stand in portions of our 19th century landscape and imagine the past. And like the nation, 19th century Newburgh had limited understanding of mental illness. If family couldn’t or wouldn’t take charge of their care. crazy people came under the authority of a town’s alms commissioners who were volunteer citizens like any municipal committee members. That’s who had been watching out for Robert Buffum for years – the alms commissioners of Salem, Massachusetts where Buffum had gone shortly after the war. Twice, one of those Salem commissioners had gone to the state hospital at Worchester to accompany him back after he had “recovered” and was released. However, recovery didn’t seem possible for the former soldier, spy and prisoner of war. A man who stood proudly to be pinned with one of America’s first Congressional Medals of Honor in 1863, fell into a tragic mix of alcoholism and paranoia.

When the Seaverns, like everyone else, couldn’t cope with him, Buffum assassinated his perceived enemy as part of the psychotic battles he fought in his mind. Held prisoner during his trial at Newburgh’s old courthouse, Buffum required extra guard details around the clock after he, seven times, jumped like a jackknife from his bunk to the stone floor trying to take his own life.

Hundreds crowded the courthouse each day of his trial and Grand Street was abuzz with reporters from all the papers of the northeast. He was convicted but found insane and imprisoned first at Sing Sing and then at Auburn where he committed suicide in July 1871.

As for the Seaverns, poor young Joseph had another nervous breakdown and had to be committed back to the Massachusetts Lunatic Asylum. Mrs. Seaverns closed up her Grand Street home, sold it and moved to Worchester to be near her son. The Arlington Paper Mill was sold and Seaverns paper machinery works closed forever.

What might have been a long and famous history for Newburgh as the national leader in innovative paper-making came to a sudden halt and, but for his murder while living among us, we might never have brought the story of the brilliant inventor, John L. Seaverns, to light.

Illustrations:

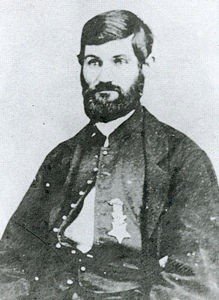

Robert Buffum wearing his Congressional Medal of Honor

An early 1870 ad for the Seaverns Paper Machinery Works