The Department of Labor was formed in March of 1913. Its purpose was to help workers, job seekers, and retirees by creating standards for Occupational Safety, wages, hours, and benefits. (1) The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) was not created until 1970. It seems that the safety and health of workers, the backbone of the Industrial Revolution, were of little concern in the 19th Century. In 1892 then U.S. President Benjamin Harris stated, “American workmen are subjected to peril of life and limb as great as a soldier in time of war”. (2)

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) began reporting and publishing new developments in accident prevention, but it was not until after World War I that BLS began to give special attention to workplace accidents and sickness. (3) By the end of the 19th century some estimates put the number of work-related deaths in the US at 35,000 annually. In the early 20th century, the trend in work-related death rates began to improve. According to Marian L. Tupy, editor of HumanProgress.org and a senior policy analyst at the Center for Global Liberty and Prosperity, this trend in workplace deaths can be attributed to “Labor union activism, including strikes and protests, has been traditionally credited with making the workplace safer. But improving working conditions cannot be divorced from the overall improvement in the standard of living. The massive economic expansion in the second half of the 19th century, in particular, tightened the labor market, and workers started to gravitate toward more generous employers. It was only after a certain critical mass of workers achieved more tolerable working conditions that more general workplace regulations became imaginable and, more importantly, affordable”. (4)

Rewind to 1869 to what today is known as Algonquin Park in the Town of Newburgh. Once the site of production of gunpowder where in 1894 they peaked at nearly 2 million pounds of powder as Orange Mills (5). The park has been a favorite for many in the area and to those of us who grew up spending a great deal of time at the park with little clue to its history as a producer of gunpowder for majority of the 19th century. The remnants of stone buildings still exist in various conditions that as much as any structure bring meaning to the old adage: “If these walls could talk.”

A Virtual Tour of Algonquin Park Today:

The walls of the various buildings are thick and are open on one side. This is reinforcement in the event of an explosion and to direct the blast out of the open side to prevent other buildings from being blown up at the same time. This does nothing to protect the worker. However, the Round House (Witch’s Castle \ Washroom) and the Superintendent’s Office and Carpenters Workshop across the street are rounded to deflect the concussion of any blast.

John Waller from Monticello had visited a friend (actually his brother-in-law David Lounsbury) who lived in the vicinity of the Mill “in which many of his boyhood days were passed.”(6) Mr. Waller produced a book in 1869 which provides the history and operations of the mill along with the details surrounding workplace-related deaths that occurred up to that time. Mr. Waller noted that annually there were 25 to 30 workers and states that there were “only 29 persons killed” in the 54 years in operation up to that point. He further notes that this is nothing compared to the Erie Railroad and that “the business is as safe if care be observed, as any other manufacturing establishment; when, however, the mischief is done it is done as quick as the powder can do it.” Mr. Waller further notes that it is the healthiest business anyone has ever worked at as no one had died from disease who worked there. One cannot read this without staring at his incredulous statement: “There has hardly been an average of two deaths in a year, and those were blown up.” (6)

Note: There is no reference data provided in Mr. Waller’s book to validate the details surrounding each of the explosions and deaths. However, several have been cited in other publications and news articles. The detail that is provided including dates and names help lend credence to the claims. The premise here being one is too many.

Ownership Timeline (Note that different publications record slightly different dates)

- 1795 to 1815 (or 1818) – Elnathan Foster: Operated as a Sawmill

- 1815 (or 1818) to 1828 – Asa Taylor: Operated as a Stamping Mill

- 1828 to 1838 – Daniel Rogers: Operated as a Powder Mill

- 1839 to 1855 – Daniel Rogers under operation by Henry Pettingill: Mill operations suspended probably after several consecutive explosions

- 1855 to 1869 – Smith & Rand Powder Company

- 1869 to 1902 – Smith and Rand merged with Laflin Powder Company assumed operations

- 1902 to 1919 – E. I. Dupont

- 1919 to 1929 – Albert Waring

- 1929 – Property sold to Frederick Delano who gifted it to the City of Newburgh in 1934 and renamed it Algonquin Park.

- 1934 – City of Newburgh

- 1978 – Turned over to Orange County

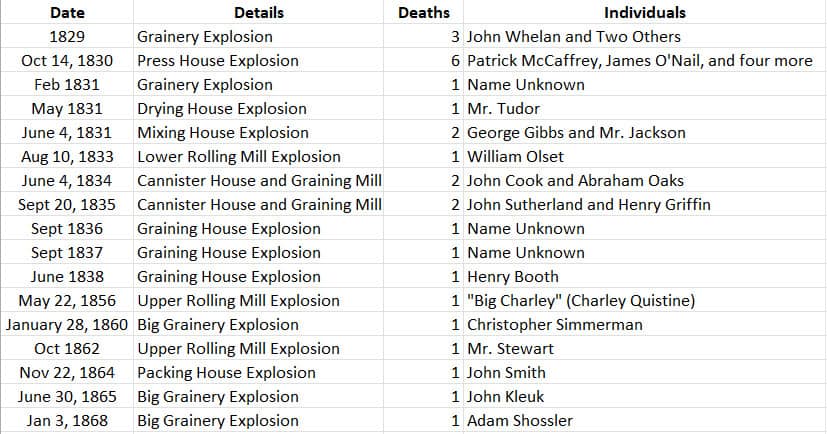

Summary of Explosions and Deaths as per Mr. John Waller as of 1869

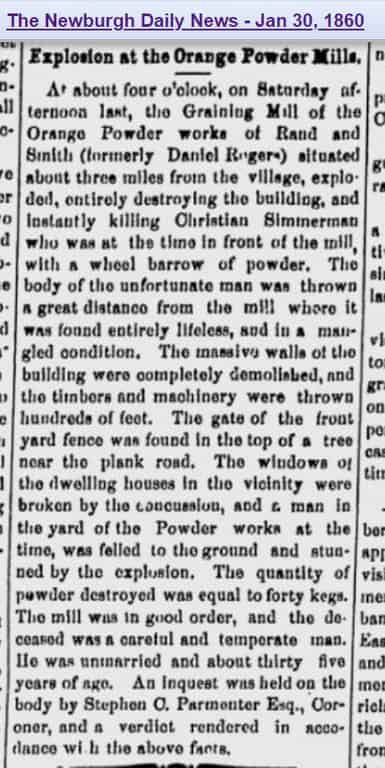

It is difficult to imagine, even if we could go back in time and understood the risks of working at such a place, that their families would benefit from the knowledge of only an average of fewer than two workers killed per year and find that somehow comforting. It is known that additional deaths occurred after the date this book was published. In the few documented cases, the blame is laid on the employee with no liability to the owners of the mill. The workers may have been treated well and most likely quite happy to have the job including a number of long-time employees. It seems as though workers were in essence nothing more than another expendable resource in the production of the powder as in other industries during the time period.

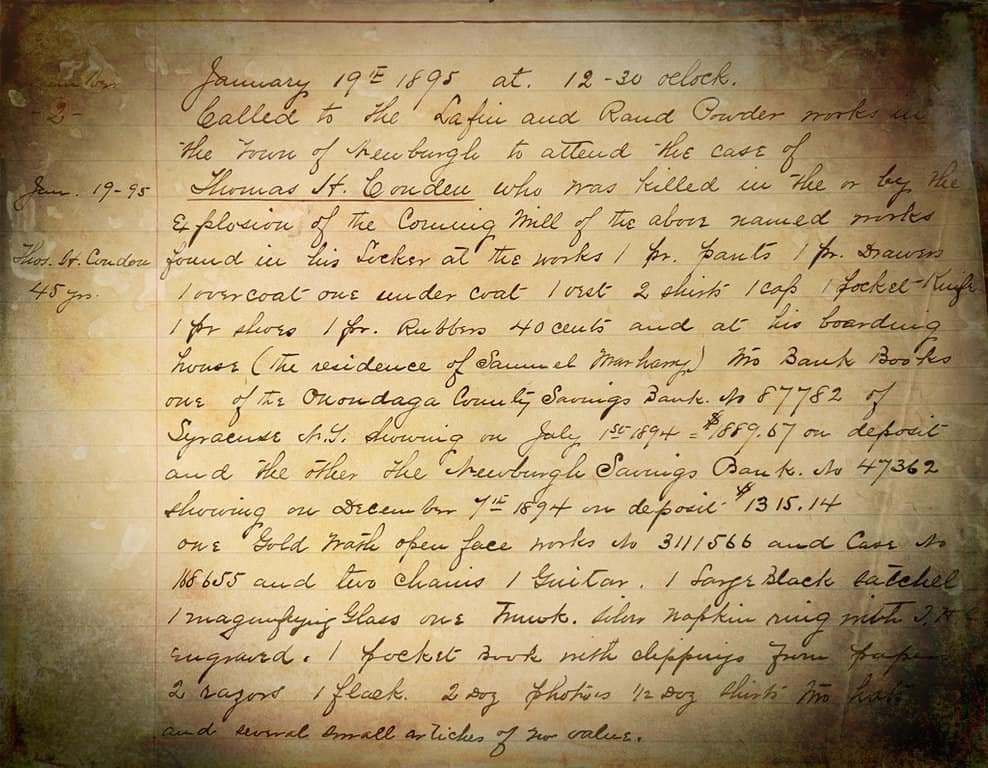

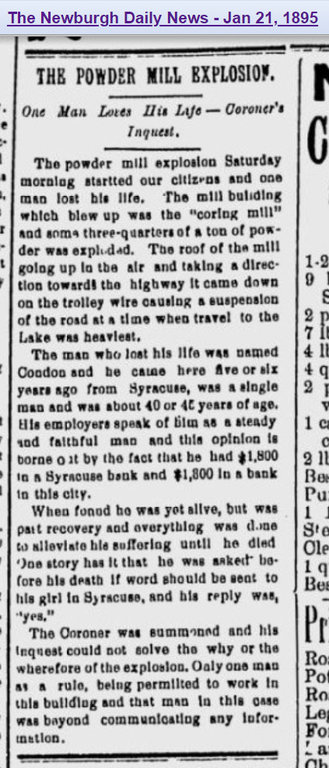

On January 19, 1895, history was repeated with the only known explosion of the Corning Mill killing Thomas H. Condon. What makes this explosion somewhat different from the others is it sheds light on the human factor in the form of a Coroner’s Report detailing the tragedy. It is also fully documented with witness statements from several other workers including 5 to 15-year employees of the mill.

Coroner:

- John J. Perrott

Doctor:

- Dr. Louis A. Harris

Witness Statements:

- William H. Smith – Superintendent

- George Handler – Employed 10 Years

- Christopher Mower – Employeed 10 Years

- Edward Hanyan – Employeed 5 Years. Worked in Glazing Mill

- John E. McGonk – Employeed 15 Years. Worked in Salt Peter Mill

- John M. Mooney – Employed 11 Years. Worked in Boiler Room

The explosion occurred at approximately 10:40 am. From the witness statements, the employees ran to the site of

the explosion and found Mr. Condon with clothes on fire approximately 25 feet away from the building. They removed the burning clothes and together carried Mr. Condon to the Superintendent’s Office (Carpenter’s Shop) which is now the historic home of Jill Enfield and Richard Rabinowitz on the other side of Powder Mill Rd. They called for the Doctor (L. A. Harris). Dr. Harris stated upon his arrival he found Mr. Condon wrapped in blankets and “writhing in pain and agony”. He stated he knew he would not survive long and gave him “medicine hyperdermically”. Dr. Harris and the others stayed with Mr. Condon until he passed around 12:30pm.

He further stated in his statement that the skin on Mr. Condon’s face was “utterly burned off” and to be “so disfigured from powder to be almost unrecognizable”. A deep cut in his forehead was sufficient to cause fracture, a fracture of the right knee, and general burn over his body causing skin to hang in shreds and burned inwardly from inhaling flames of burning powder. “Either of which was sufficient to cause death”. The statements from the other witnesses echoed that of Dr. Harris. They each assisted Mr. Condon and helped to carry him to the Carpenter Shop.

Whether or not Thomas H. Condon had family, where he is buried, or other information about the man is not currently available. He is just one example of many that occurred at the site. His death provides insight into the risk associated with this type of work but also the attitude of employers and the country as a whole where production was important and perhaps the lives of workers were not so important. Certainly, the other workers were devastated by these explosions. They probably also worried that they would be next. They knew the risks but needed the work.

There was no Bureau of Labor Statistics, no Occupational Safety and Health Association, no inspections, and plenty of blame to go around.

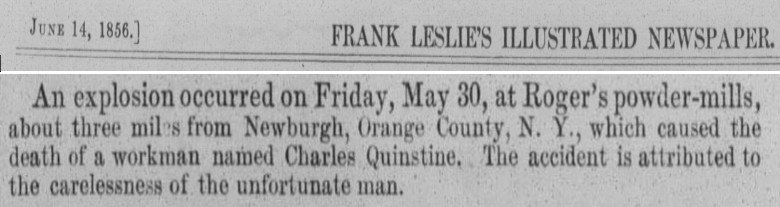

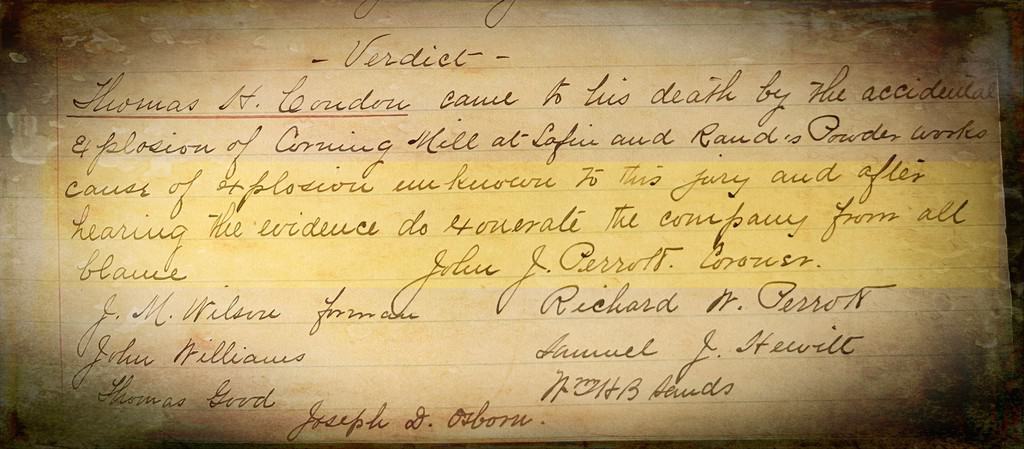

From what little documentation exists it is the worker’s fault. As with the May 1856 explosion killing “Big Charley” Quistine, “The accident is attributed to the carelessness of the unfortunate man”. The verdict in the Thomas H. Condon death was that the cause of the explosion was “unknown”.

Yet after hearing the evidence it was concluded that “the evidence do exonerate the company from all blame”. After almost 100 years of operation and more than 29 deaths, no one was held accountable that we know of. As we all walk around this beautiful park today, perhaps we can give some remembrance both to the history and to the lives lost, which were NOT acceptable.

Update June 2, 2025: Since posting this blog I’ve come upon another sad chapter in the history of explosions at Algonquin Park. Town of Newburgh Historian @Alan Crawford had asked for some assistance and after some extensive searching we found a news article in an 1871 Port Jervis Newspaper ( Port Jervis’s Tri-States Union edition Vol. XXI, No. 49, published September 29th, 1871) graphically detailing the event that occurred.

References:

- US Department of Labor (dol.gov)

- The Rise and Fall of American Growth, The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War, By Robert J. Gordon · 2017

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics (bl.gov)

- Workplace Fatalities Fell 95% in the 20th Century. Who Deserves the Credit?; by Marion L. Tupy, 2018

- Algonquin Powder Mill Park – Orange County Historical Society Journal, by former Town Historian Leslie P. Cornell, Vol 20 Nov 1, 1991

- The Smith and Rand Powder Company, Where and How Powder is Made: by John Waller Sr., 1869

Additional References

- 1895 Coroner’s Report – Orange County. Doctor Louis A. Harris, January 19, 1895, Courtesy of the Newburgh Historical Society

- Algonquin Park – by Former Town Historian Ed Stotesbury, Courtesy of Brenda Caparasso

1 thought on “The “Acceptable Losses” at Orange Mills (aka Algonquin Park): by Joe Santacroce”

Fabulous article! I have so many wonderful memories of the park as a child and still go there for picnics and dog walks.