The Robinsons of Newburgh

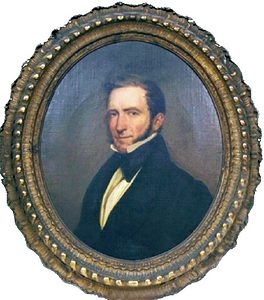

Each day, thousands of people walk and ride along a main route through Newburgh: Robinson Avenue, part of Route 9W. Few know the origins of the street name nor the importance of the man for whom it was named. Henry Robinson lived a life as full of adventure, success, danger, love, and tragedy as any our community can chronicle. He was a merchant seaman, a trans-Atlantic ship captain, a wounded war veteran, a scientific farmer, a sports enthusiast, and a major philanthropist in 19th century Newburgh.

Born in 1782 in the little village of Linlithgow in Columbia County, he went to sea at an early age as did so many Hudson Valley youth. In New York City, he met and married Ann Buchan and they had two daughters, Mary and Sarah. They lived on the west side of lower Manhattan and he advanced his maritime career to become a shipmaster (captain) of packet ships that carried freight and passengers, a lot of responsibility for a young man just entering his 30’s.

Henry’s sailing skills brought him into the War of 1812. In January 1815, when his second child, Sarah was only 5 months old, he was recruited to help break through the British blockade of New York Harbor. He boarded the naval frigate, USS President, to assist its escape into the open seas beyond New York. The captain of the President was the renowned Commodore Stephen Decatur, Jr. In a snowy gale that they hoped would provide cover on the 14th of January, Henry succeeded in helping the USS President make it out past Sandy Hook and over a treacherous sandbar but the American flagship was spotted by a British naval squadron, chased and attacked by five man-of-war frigates.

From early morning until nearly midnight, a brutal naval battle was waged out on the decks in frigid winds. Canon fire shredded sails and masts and killed and injured many. The President was finally crippled by enemy fire and the English towed her and her injured crew to their fort in Bermuda. The dead were buried at sea and Henry, along with a wounded Commodore Decatur and the rest of the surviving crew were held as prisoners of war – but not for long.

News finally reached Bermuda that the war had ended with the Treaty of Ghent, signed on Christmas Eve, 1814, before their awful battle ever began.

Captain Robinson made it home to his wife, Ann, and his little daughters and resumed his career as a freighter. He captained several packet ships, the main mode of commercial transportation, throughout his sailing career in the 1810s into the 1830s. His main route was from New York to le Havre  on the Normandy coast of France carrying the trade goods desired by households in Europe and America.

on the Normandy coast of France carrying the trade goods desired by households in Europe and America.

In 1824, he was selected to be the captain to bring Revolutionary French General Lafayette to America for his celebrated return tour of the United States. Lafayette was delayed at home and had to sail on a later ship. The two men obviously knew each other, however, since they corresponded and traded plant and animal species over the years as they each worked at their second careers as scientific farmers. The Marquis’s estate, LeGrange, was in Normandy.

In anticipation of Lafayette’s visit to New York, Robinson presented a portrait of the French hero to the City of New York to hang in City Hall.

Henry and Ann raised their daughters in New York but suffered the tragedy of their early deaths. Their youngest, Sarah, died at the tender age of 15 while on a family trip to Paris. The parents accompanied her body on the voyage home and purchased a plot for her burial in Newburgh’s Old Town Cemetery. Just over a year later, her older sister, Mary, aged 19, married James Benkard, a German-American merchant of fine French goods, and they settled into a Gramercy Park home where they had six children. When Mary died suddenly in October 1841 at the age of 29, her body was brought to Newburgh where her parents had settled and she was buried beside her sister.

In 1824, Henry and Ann purchased land on the south Newburgh border (between Renwick Street and the Quassaick Creek) from Henry’s brother-in-law, William Gardner. They moved in once Henry gave up his trans-Atlantic trade. He cleared 100 cords of wood from his new lots and took to farming with the same enthusiasm he had given to his mastery of the seas.

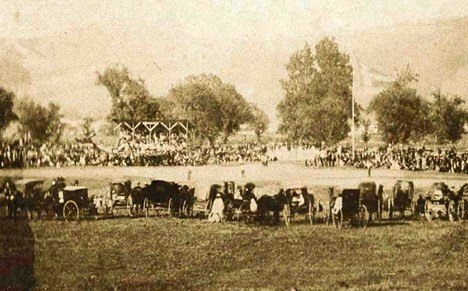

In south Newburgh, Robinson raised many crops and livestock. His property included a brook and a pond in which he raised fish – including carp he brought to America from Holland. Henry was a founding member and officer of the Horticultural Association of the Hudson Valley and of the Orange County Agricultural Association. His acres were used for agricultural fairs at which local farmers displayed their produce and animals. The reports of these fairs give us a sense of Robinson’s farm which extended up into the neighborhood now called “The Heights.” He won prizes for wheat and dairy cattle and, at age 65, won first prize in the plowing competition.

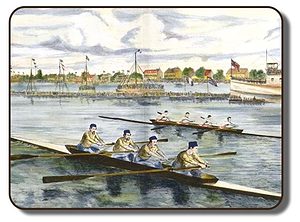

Captain Robinson was also an avid sportsman. From a life on deck, he loved sailing and rowing races. In 1824, before he moved up to the Hudson Valley, he was the judge of a rowing race off The Battery at Castle Garden.

In Newburgh, he started the annual Newburgh Regatta and challenged New York City rowing clubs to come upriver to compete. He coached his new teams into the winner’s circle in just three years of competition. One of his first Hudson River regattas in 1837 was staged to raise money for Newburgh’s public library. Henry paid for the racing shells as well as the bright silk uniform shirts of the Newburgh rowing teams.

He loved to root for his oarsmen and could be heard shouting “Bully!” as they pulled ahead. That expression became the nickname of Bully Robinson in his later years in Newburgh.

Robinson also supported the birth of local baseball, becoming the patron and vice-president of the Hudson Rivers, Newburgh’s first touring team. A section of his farm was converted into a baseball diamond including wooden bleachers for folks to witness the thrill of the new sport.

Newburgh village minutes record the gifts supplied to the community by the Robinsons, particularly the annual contribution of sand from his farm’s extensive sandbanks to help with road improvements. He also gave land valued at $6,000 along his Hudson River shoreline for the development of the Erie Railroad. Understanding that rail would quickly compete with steamboats, Henry was one of the Erie’s major investors to help connect Newburgh to growing markets.

Mrs. Ann Buchan Robinson died in Newburgh in 1853 at the age of 61 and her husband commissioned an elegant mausoleum to be prepared for her burial. There is no certainty of the architect, but Henry would have had America’s best to choose from since Newburgh was maturing  as a center for innovative building and landscape design. The Robinson tomb is constructed in the Egyptian Revival style popular in the early 19th century following Napoleon’s expeditions to Egypt. A legend has grown that the tomb was the fulfillment of a promise Henry had made to Ann that he would someday build an elegant new home to replace their rambling old frame farmhouse.

as a center for innovative building and landscape design. The Robinson tomb is constructed in the Egyptian Revival style popular in the early 19th century following Napoleon’s expeditions to Egypt. A legend has grown that the tomb was the fulfillment of a promise Henry had made to Ann that he would someday build an elegant new home to replace their rambling old frame farmhouse.

In 1855, Henry married again to Mary Van Alen of Kinderhook, daughter of John Van Alen, an old colleague of Robinson’s in the freighting business. The 1860 census lists Henry and Mary still living on their south Newburgh farm with two farmhands and two house servants.

Robinson’s scientific mind continued to be engaged in the 19th-century quest for exploration. New trade routes to the Pacific were sought in the far reaches of the oceans and navigators were competing to find a reliable “northwest passage” to avoid the long voyages around South America. Robinson endowed an 1860 expedition to the Arctic that scouted out possible sailing routes around the northern reaches of Canada. He even gave his yacht, the Victoria, to Captain Hail who made the voyage. To this day, there is a Robinson Sound in the territory of Nunavut around the Boothia Peninsula of what had been called King William’s Land.

When the Civil War broke out, Henry saw his grandsons join the fight. Mary Robinson Benkard’s children had grown and Captain James Benkard, Jr. fought with the 7th NY Regiment and then served on the staff of Newburgh’s own Major General John E. Wool. Another grandson, Henry Benkard, served in the Sea Coast Artillery in the war.

Perhaps Henry remembered his battle off Long Island when he thought of his grandson manning that battery. Captain Robinson generously contributed to local aid societies that supported the families of men away fighting in the war and then contributed to their welfare when they returned home.

On March 9, 1866, at the age of 84, while walking to the Newburgh polling place to vote, Henry Robinson suffered a stroke. He was carried home where he died a few days later. Captain Robinson’s body was the last to be laid to rest inside the family mausoleum in Old Town Cemetery. In the ancient architectural style he chose, the doorway is crowned by the Egyptian symbol of immortality. It is a fitting image for a man whose life followed the arc of 19th century America and whose enthusiasm and charity helped to carry his adopted hometown into the future.

By Newburgh City Historian Mary McTamaney

November, 2021

Contact: NewburghHistory@usa.com